How Age Affects Your Circadian Rhythm

- Circadian rhythms shift with age, gradually becoming earlier in older adulthood.

- Natural changes in combination with lifestyle can lead to different sleep timing preferences.

- Older adults spend less time in deep sleep, often leading to sleep disruptions and daytime sleepiness.

- External factors, like daylight exposure and physical activity, can also impact your circadian rhythm.

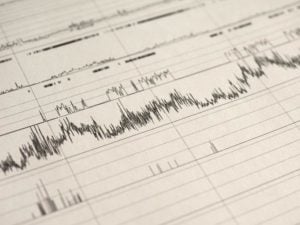

For most people, sleep-wake cycles follow the sun. As daylight breaks and temperatures get warmer, we wake up. As darkness falls, core body temperature drops and the body produces a hormone called melatonin that promotes sleep. This daily pattern is known as the circadian rhythm and, just like our minds and bodies, it tends to change with age.

How Do Our Circadian Rhythms Change with Age?

Circadian rhythms shift throughout our lifespan, peaking in lateness during adolescence and then gradually shifting back as we age. Changes to the circadian rhythm are a common cause of sleep problems in older adults.

Starting at age 60 to 65, circadian rhythms get earlier . Known as a phase advance, this shift means that older adults perform mental tasks better in the morning and start to get sleepy earlier in the evening. Research also shows that circadian rhythm timing in older adults is more delicate, leading to fitful sleep if they don’t sleep within certain times.

What Does Sleep Look Like in Older Adults?

According to their internal body clock, most older adults need to go to sleep around 7 p.m. or 8 p.m. and wake up at 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Many people fight their natural inclination to sleep and choose to go to bed several hours later instead. Unfortunately, the body clock still kicks in and sends a wake-up call around 3 a.m., resulting in disturbed sleep from that point onward.

In terms of sleep quality, older adults spend more time in light sleep and less time in deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Light sleep is less restful, so the average older adult will wake up three or four times a night. It’s common for older adults to wake up and fall asleep more suddenly compared to younger adults, leading to the feeling that you are spending most of the night awake.

On the whole, older adults get much less sleep on average than younger adults, even though their sleep needs are actually the same. Most older adults sleep only six-and-a-half to seven hours a night, falling short of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s recommendations . Older adults also seem to have more trouble adapting to new sleep rhythms, so changes to their schedule might be more difficult to manage.

Sleep deprivation can make you tired, confused, and even depressed, symptoms which may be mistaken for dementia or other disorders. While it’s normal to experience sleep problems as you age, severe changes to your circadian rhythm may be an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease .

The Science Behind Aging and Circadian Rhythms

Researchers still don’t know for sure why the circadian rhythm shifts earlier as we age, but it’s likely a combination of biological and environmental factors. In later adulthood, outside cues for the circadian rhythm appear to become less effective. Researchers believe that certain clock genes may lose their rhythm and be replaced with other genes that act a little differently.

Since light plays such a critical role in regulating the circadian rhythm, many studies have focused on how light exposure changes as we age. It may be that aging eyes don’t let as much light in, particularly the short-wave light that is important for regulating the circadian rhythm. It might also be that we spend less time outdoors and more time in weak artificial light, which is not as effective at controlling our sleep-wake cycle. Cataract surgery lets more light into the eyes and seems to improve sleep quality.

Additional considerations apply to residents of care homes, as they may spend less time outside in the sunlight and tend to be less active. Adults staying in long-term institutions may find themselves disturbed by noise and light during the night, especially if they share a room with someone else. Compared with more independent adults, care home residents are more likely to suffer from poor sleep and may spend most of the day drifting in and out of sleep.

How To Cope With Changing Circadian Rhythms as We Age

It is very difficult to fight the natural inclination of your body to sleep at certain times, so the easiest way to get better sleep as you age may be to shift your sleeping pattern earlier. You may be able to achieve sounder sleep by going to bed and waking up at the same time every day.

Getting more light during the day may help you sleep through the night. If you prefer to go to sleep later, try not to get too much light in the morning hours. Instead, go for an evening walk or use light therapy later in the day. This can help delay the release of melatonin and “trick” your body into delaying your bedtime.

Sleep Hygiene Tips for Older Adults

An easy way to improve sleep is by adopting sleep hygiene habits that strengthen the circadian rhythm and create a mental association between bed and sleep. To start sleeping better, experts recommend:

- Keeping the bedroom cool, dark, and quiet

- Avoiding and limiting alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco after lunch

- Avoiding liquids and large meals before bed

- Limiting naps to early in the day and a maximum of 30 minutes

- Eating a healthy diet with plenty of fruits and vegetables

- Getting daily exercise, preferably outside

- Turning off the TV and other screens an hour before bed

- Keeping the bed for sleeping and sex only

- Getting out of bed and doing something else if you can’t sleep

You should also make it a priority to treat any underlying sleep disorders or other conditions such as chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, or prostate disorders. Talk to your doctor to see if you can adjust your medication schedule to minimize the effects on your sleep. In the short term, your doctor may prescribe melatonin supplements or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) to help re-establish a healthy sleep pattern.

References

10 Sources

-

Fischer, D., Lombardi, D. A., Marucci-Wellman, H., & Roenneberg, T. (2017). Chronotypes in the US – Influence of age and sex. PloS one, 12(6), e0178782.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28636610/ -

Duffy, J. F., Zitting, K. M., & Chinoy, E. D. (2015). Aging and Circadian Rhythms. Sleep medicine clinics, 10(4), 423–434.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26568120/ -

Anderson, J., Campbell, K. L., Amer, T., Grady, C. L., & Hasher, L. (2014). Timing is everything: Age differences in the cognitive control network are modulated by time of day. Psychology and aging, 29(3), 648–657.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24999661/ -

Li, J., Vitiello, M. V., & Gooneratne, N. S. (2018). Sleep in Normal Aging. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 13(1), 1–11.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29412976/ -

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (2020, July 19). Aging changes in sleep. MedlinePlus.

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004018.htm -

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979105/ -

Musiek, E. S., Bhimasani, M., Zangrilli, M. A., Morris, J. C., Holtzman, D. M., & Ju, Y. S. (2018). Circadian Rest-Activity Pattern Changes in Aging and Preclinical Alzheimer Disease. JAMA neurology, 75(5), 582–590.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29379963/ -

Chen, C. Y., Logan, R. W., Ma, T., Lewis, D. A., Tseng, G. C., Sibille, E., & McClung, C. A. (2016). Effects of aging on circadian patterns of gene expression in the human prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(1), 206–211.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26699485/ -

Figueiro M. G. (2017). Light, sleep and circadian rhythms in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Neurodegenerative disease management, 7(2), 119–145.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28534696/ -

Chellappa, S. L., Bromundt, V., Frey, S., Steinemann, A., Schmidt, C., Schlote, T., Goldblum, D., & Cajochen, C. (2019). Association of Intraocular Cataract Lens Replacement With Circadian Rhythms, Cognitive Function, and Sleep in Older Adults. JAMA ophthalmology, 137(8), 878–885. Advance online publication.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31120477/